The Papua Blog

The Discovery of Papua

About colonists and adventurers

Words by Marc Weiglein, photos by Marc Weiglein and others

New Guinea was one of the last terra incognita of our planet. The discovery of New Guinea was gradual and slow, as if the island did not want to share its secrets with the world. On maps from the 70s and 80s, large parts of the country were still shown as white spots or labelled with ” insufficient data”. Some stories of the first explorers are world-famous and continue to fascinate every listener to this day. These stories are the subject of this article. But first a quick glance at the beginnings.

When does the discovery of Papua begin?

Like many other stories of discovery, the story of the discovery of Papua begins with the fact that in 16th century Europe a gram of cloves was more expensive than a gram of gold. The European kingdoms sent countless ship expeditions around the globe, and especially the islands of today’s Indonesia – rich in pepper, cloves, cinnamon – were incredibly valuable.

So it was also Europeans, Portuguese to be exact, who in 1526 on their way to the Maluku Islands sailed past the coast of New Guinea for the first time. They did not go ashore then, but this first mention of Papua paves the way for further European expeditions.

Legend has it that Papua received its name from the Portuguese or the Spanish. They referred to the native word “papu”, which means “frizzy” and describes the hair of the locals.

In 1793, the British Empire tried for the first time to colonize New Guinea on the western part of the island. The attempt failed and the British withdrew again. Only in 1828 the Netherlands succeeded in a permanent colonization of some coastal regions of Papua. Papua became part of Dutch India, the precursor of today’s Indonesia. The border between the western and eastern parts of New Guinea, which still exists today, is a relic from the colonial period. While the western part of New Guinea was claimed by the Netherlands since 1828, the northeastern quarter of New Guinea was claimed by Germany and the southeastern quarter by Great Britain from 1884. In 1895 Great Britain and the Netherlands finally signed a border treaty. The border, which was established at that time and runs straight through the middle of the island, has remained in place until today.

For a brief explanation of the terminologies, please read our blog entry: Papua, West Papua, PNG…

New Guinea, an island for explorers

New Guinea was not only interesting for colonists and traders, but also aroused the curiosity of explorers and scientists early on. Especially considering the fact that the colonies only existed along the coasts, while the entire interior of the island remained a mystery for a long time.

New Guinea has an extremely rich flora and fauna. But not only that! New Guinea is also ethnically and culturally unique. The diversity of languages and isolated cultures is greater than anywhere else in the world. Therefore, we cannot even speak of a “Papuan culture”. Each area is home to different tribes; each tribe has its own language, traditions, beliefs, rituals. For New Guinea a total of over 300 own languages (!) have been identified. Many of these languages are spoken by only a few thousand, if not only a few hundred people.

The unique flora and fauna and the cultural diversity, coupled with the extreme isolation of the island, quickly attracted many explorers and researchers. And then there was the story of Jan Carstensz.

Jan Carstensz – the man who saw snow

Not much is known about the Dutch explorer Jan Carstensz. We know that he belongs to the Dutch East India Company (also called VOC – Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) and was stationed in Ambon on the Maluku Islands when the VOC assigned him in 1622 to lead an expedition into the waters of New Guinea.

Carstensz was assigned to explore the southern coast of the “great country of New Guinea” and to verify the records of his colleague Willem Janszoon. Janszoon had sighted Australia a few years earlier, on an expedition along the coast of New Guinea, and had told his employers about it. Janszoon was wrongly convinced that New Guinea and Australia are parts of a coherent landmass (Dutch maps will be drawn with this error for many years to come).

Carstensz’s expedition lasts for over a year and is not very successful. During a stopover on the coast of New Guinea the crew is attacked by natives and several crew members loose their lives. Nevertheless, the Dutch explorer sails further towards Australia and goes ashore several times. Again there are clashes with the native population. Carstensz is able to capture some of the attackers and decides to take two of them to Batavia, the former name of Jakarta, where the VOC is based. When Carstensz is about to discover the passage between New Guinea and Australia, he encounters headwinds and decides to return.

Apart from trouble with the natives, Carstensz does not find much on the Australian coast. His official report is therefore quite negative and will have a discouraging effect on further exploration of this region by the Netherlands for some time to come.

Since Carstensz does not find anything of interest on his shore excursions, and since he is also denied to discover the passage between Australia and New Guinea, his expedition almost fell into oblivion. But this did not happen. Instead, his name today is in the history books for a discovery that Carstensz made on his way back, for which he was mocked and called a fool in his homeland at the time: Jan Carstensz had seen snow.

On February 16, 1623, Carstensz stood on the deck of his ship and looked east, and as he noted in his diary, “we were about 1½ miles from the lowlands, in 5 or 6 fathoms, loamy ground; at a distance of about 10 miles, according to estimates, inland, we saw a very high mountain range which was snow-white in many places, which we thought was a very unique sight, since it was so close to the equinox line”.

Carstensz referred to the snow-covered peaks of the mountains of New Guinea which we now know as Puncak Trikora, Puncak Yamin and Puncak Mandala. And of course the highest of them, the one that now bears his name, the Carstensz Pyramid (Puncak Jaya).

Nobody in Europe at that time could imagine that there could be snow-covered peaks near the equator, and it had to take another 200 years before his statement could be verified. Better late than never.

More than 300 years had to pass until the Austrian Heinrich Harrer succeeded in the first ascent of the Carstensz Pyramid.

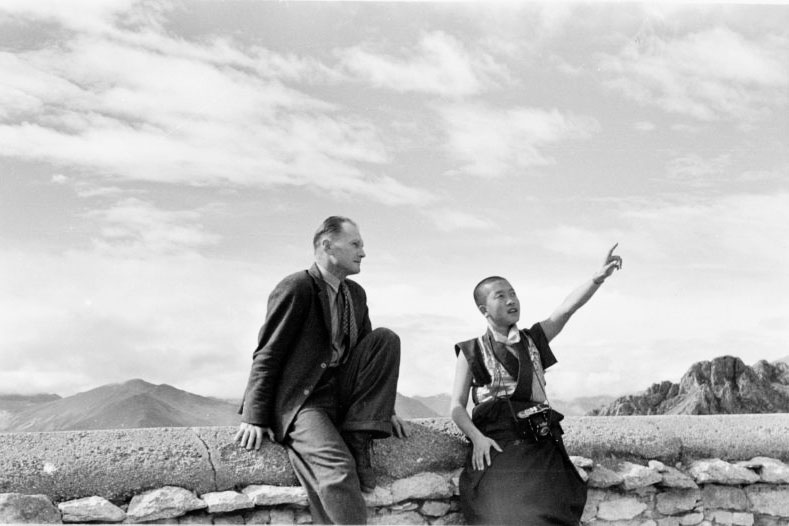

Heinrich Harrer – His life in the stone age

Heinrich Harrer achieved fame around the globe through numerous first ascents. One of his greatest achievements remains the first ascent of the Carstensz Pyramid, which he achieved in 1962. But not only that. He also escaped from captivity in British India to Tibet and became friends with the Dalai Lama. Harrer’s book “Seven Years in Tibet” became a classic and was made into two movies.

The Carstensz Pyramid is with a height of 4,884 meters (16,023 feet) the highest peak in Oceania and belongs to the famous group of the 7 Summits. The first attempt to climb it by a Dutch expedition in 1936 failed. At the time the group could not agree which of the three summits in the mountain range was the highest. They first climbed Ngga Pulu and then East Carstensz. When trying to reach the third peak, the Carstensz pyramid, the group got into bad weather and had to retreat.

Lucky for Harrer, who was the first to make his way through the glaciers to the summit in 1962. At that time, just as during the Dutch expedition before, it was still not clear that the Carstensz Pyramid was indeed the highest peak. In fact, it was only in 1994 that the Carstensz Pyramid was confirmed and generally accepted as the highest peak.

Harrer was accompanied by a diverse team, including geologist Jean Jaques Dozy, who, when he saw a strangely dark and green colored peak, realized that it must be a mountain of gold and copper ore. This will later become the largest gold mine in the world.

Until today the Carstensz Pyramid has not been conquered by many mountaineers. And this is only partly due to the fact that from 1995 to 2005 access to the area was prohibited. Even after the opening, a lengthy permit procedure is necessary and the climb itself is extremely demanding.

The above mentioned “Seven Years in Tibet” is Harrer’s most famous book, thanks to the filming of the same name with Brad Pitt – but by far not the only one! Harrer has recorded his adventures in over 20 books and especially his works about the expeditions in Papua became classics. Particularly noteworthy is the “I come from the Stone Age” about Harrer’s ascent of the Carstensz Pyramid.

But in New Guinea Heinrich Harrer did not only climb the Carstensz Pyramid.

Further expeditions, many of them with an absolute pioneering character, bring Harrer as one of the first foreigners to the Baliem Valley and the Asmat area, to name a few. For months Harrer fights his way through the brutal wilderness. He gets seriously ill, falls, breaks 32 bones in his body, barely gets away with his life, only to set off again into the jungle some time later. Exciting stories about these adventures with precise explanations of the conditions at the time can also be found in Harrer’s publications.

But Harrer was not the only known name to plunge into the New Guinea adventure in the 1960s. A young man with a much more famous name was also traveling in New Guinea at that time. Unlike Harrer, he will not leave the island alive. His name: Michael Rockefeller.

Interested in an expedition to the Carstensz Pyramid? We have been one of the most reliable operators for the famous summit for years. We do not only sell the trip, we also lead it ourselves! Click here for the program: Carstensz Pyramid Expedition

Michael Rockefeller and his dangerous love for primitive art

Was Michael Rockefeller killed, butchered and eaten by Asmat cannibals? What sounds like a Hollywood screenplay may have actually happened. The Rockefeller file has been a mystery for 60 years and it seems increasingly unlikely that there will ever be a clear explanation for Rockefeller’s mysterious disappearance. Nobody knows the truth or nobody wants to talk about it.

Michael Rockefeller was 22 years old when his father Nelson Rockefeller, the current governor of New York, ran for the presidency of the United States in 1960. As a Rockefeller, Michael is part of the most wealthy and powerful family in the world at the time. Michael’s parents are the leaders of New York’s upper class and important patrons of the arts. Of great importance for Michael’s later fate is the opening of the Museum of Primitive Art in 1957 by father Nelson Rockefeller. Nelson is an ambitious collector of so-called “primitive art” and would like to make his collection accessible to a broad public. The Museum of Primitive Art is the first renowned museum of its kind and will make a significant contribution to influencing the general perception of primitive art. What was previously dismissed as “junk” will suddenly become an independent, valuable art form in its own right that deserves to be exhibited in Manhattan. A milestone in modern art history!

Michael is a good student at Harvard University, and his family expects him to pursue a career in finance after graduation. But Michael is also fascinated by the raw art from all over the world, which can be admired in his father’s museum. He was soon appointed to the museum’s board of directors and in 1961 his inherited passion and thirst for adventure finally led him to Papua. On his first trip to New Guinea, he accompanied his student friend, the filmmaker Robert Gardner, to work as a sound engineer on his film project Dead Birds. For 6 months the Dani tribes of the Baliem Valley are documented, and Michael is right in the middle of it. When a shooting break is due, Michael travels to the Asmat area in southwest Papua for the first time. During a meeting with the director of the Dutch National Museum of Ethnology, Michael hears about the unique carving art of the headhunter tribes there. His interest is awakened.

When filming ends in September, Michael returns to the USA, only to set off again for New Guinea a month later. As befits a Rockefeller (and probably also to impress his mighty father), Michael has great ambitions this time: From the Asmat he wants to bring back the largest collection of primitive art that has ever existed for his father’s museum.

Thus, at the end of 1961, Michael Rockefeller finally ends up on a catamaran in the Arafura Sea, accompanied by his friend, the anthropologist René Wassing, and two native Papuans, with the intention of buying these amazing Asmat wood-carved shields, paddles, statues, or even these fascinating, several-meter-high ancestor poles that he had previously seen on a scouting trip.

The group sails along the south coast and visits several dozen Asmat villages. It is said about this “shopping trip” that Michael is too greedy and ambitious and often misses the most important aspects. He does not try to understand the culture of the Asmat, the meaning of their art. He only sees the beauty of the art and wants to acquire as much of it as possible and send it home by the fastest way. Perhaps it is also this short-sightedness that later becomes his fate.

In addition to the ancestor poles and wooden shields, it is especially the headhunting trophies of the Asmat that arouse Rockefeller’s special interest. The young man offers great rewards for every skull that is brought to him. Michael’s efforts are not popular with Dutch officials, as they reignite the headhunting among the Asmat. One official reports:

“Rockefeller’s presence is causing a huge increase in local trade, especially the demand for beautifully painted, preserved heads has increased.”

Meaning: The Asmat go head hunting to exchange the newly captured skulls for machetes and tobacco with Rockefeller. Michael collected dozens of pieces.

Michael’s journey ends abruptly when his wooden catamaran capsizes on November 18, 1961, during a voyage between the coastal villages of Agats and Atsj due to heavy swell. Rockefeller, Wassing, and the two local companions (two teenage boys) drift rudderless towards the open sea. The two Papuans understand the situation immediately and shortly after the accident they swim towards the shore to seek help. Rockefeller and Wassing stay behind on the capsized catamaran. The night falls and passes by. The next day begins and passes by. Rockefeller soon assumes that the Papuans have not succeeded. He becomes restless and considers swimming to the shore himself. The shore is still visible at this time, but every hour it seems to be further away. Against his comrade’s opinion, Rockefeller makes the decision to swim to the shore, which he estimates to be 8 kilometers (5 miles) away. With an empty petrol canister tied around his waist, Michael leaves the catamaran and swims away.

It is the last time Michael Rockefeller is officially seen.

Rockefeller’s body is still missing today. The authorities concluded that Michael died while swimming towards the coast. Probably he drowned or was attacked by a crocodile, according to the official explanation at that time.

But some testimonies, which were kept secret, tell a different story about the death of Michael Rockefeller.

The 2 Papuans could actually reach the shore and get help. René Wassing is finally rescued a few hours after Michael’s departure. Since the Dutch authorities and the Rockefeller family are quickly informed about the disappearance of Michael Rockefeller, boats, planes and helicopters soon begin patrolling the south coast in search of Michael. The Australian Navy, and later the American Navy support the search. Several thousand locals are also assigned to search the swampy mangrove forests along the coast on foot or by dugout canoes. Nelson Rockefeller charters a Boeing plane from New York to travel with his daughter and a group of journalists via the Papua Island Biak to Merauke, where the task force is set up.

The Arafura Sea is a shallow, muddy sea with a high water temperature and the search parties still hope to find Michael alive.

But all efforts remain unsuccessful. Although the empty petrol canister is found, there is no further trace of Michael himself, dead or alive. After 10 days the family decides to stop the search for Michael, and they return to the USA in despair.

The story officially ends here, but the disappearance of the son of the richest man in the world was further investigated after the Rockefellers’ departure, with disturbing results.

The first one to set out on the search for further traces at the behest of the Dutch government is officer Wim van de Waal. Rockefeller had bought the capsized catamaran from van de Waal and it can be assumed that he had a high personal motivation to find out more about what happened. Furthermore, van de Waal knows the area well, he has been there for a long time and speaks the Indonesian language. He spends 3 months searching for clues. His investigations bring frightening things to light. For van de Waal it is clear that Michael Rockefeller was killed and eaten by the Asmat.

These allegations are hard to believe. At that time, the Asmat were still cannibals, belligerent and aggressive. But these aggressions were never directed against white people. Too great was the respect for modern weapons, and too high was the interest in the tempting trade objects. That of all people a Rockefeller, unarmed and in distress, could be the first white man to die a violent death, that was simply unbelievable.

But it is not only van de Waal who voices such allegations. Only a few weeks after Michael’s disappearance, the Dutch missionary priests Cornelius van Kessel and Hubertus von Peij actually told the Dutch authorities the same story. Priest Hubertus von Peij, who has lived in the Asmat region for years, was well known and respected by the tribes there. One night 4 Asmat men came to his door to tell the priest a story. With relevant details they told him how a white man with glasses and unusual clothing was killed by the men of the Asmat village Otsjanep.

This murder is said to have been an act of revenge. But an act of revenge for what? Rockefeller had not been around for long and he was just a harmless collector who had never come into conflict with the Asmat.

The incident on which the theory of the act of revenge is based dates back already 4 years. At that time, the Dutch colonial governor of the Asmat region, Max Lepré, had organized a raid against the Asmat villages Omandesep and that very Otsjanep. These two villages were often involved in headhunting and mutual massacres, and Max Lepré planned to frighten them and confiscate their weapons. But things took a turn for the worse when men from the village of Otsjanep started to attack, and as a result some of the most influential and powerful men in the village were shot by Lepre and his crew. In the universe of the Asmat such actions must be avenged, otherwise the spirits of the dead will make life hell for the living. And 4 years later the spirits of these men still have to be avenged.

Carl Hoffman, author of “Savage Harvest: A Tale of Cannibals, Colonialism, and Michael Rockefeller’s Tragic Quest For Primitive Art”, traveled to Papua several times, spent several months in the Asmat region, and learned the local language to seek the truth. He takes up the old trail and comes to similar results.

Hoffman suspects that Michael meets a group of men from that Otsjanep village near the shore. He is helpless, he is alone, and he is a white man. For the act of revenge it is not important at this moment that Michael has nothing to do with the incident 4 years ago. The chance is just too good, it must be taken. The men kill the white man, they ritually cut him up, rub his blood on themselves, eat his brain and flesh, and divide his bones among themselves. Just like they always do after a successful headhunt.

Some pictures taken by Michael himself during his earlier scouting trip prove that he had already met these men. This could be a further indication that he was indeed killed in a ritual act of revenge. In fact, the Asmat only take the bones of people they know.

The Dutchman Wim van de Waal is said to have even succeeded in finding some of Michael’s bones during his investigations, which were distributed to the men from Otsjanep after his death. He hands them over to the Dutch authorities as evidence. But we are in the year 1962, the handover of Papua to Indonesia is in preparation and Nelson Rockefeller is running for the US presidency a second time. Neither the Rockefeller family nor the Dutch authorities have any interest in a cannibalism story with macabre details taking over the world press.

The evidence is kept secret, van de Waal is withdrawn, and the two priests are ordered by the Catholic authorities to remain silent.

Even among the Asmats, the story remains taboo. In fact, the Asmat firmly believe that they have been punished for the murder of Michael Rockefeller. Right after Michael’s death, they saw helicopters for the first time – monsters of steel hovering right over their heads! Warships and planes are looking for him. In every village they ask for him. Rockefeller is not just any colonial official. What a crazy coincidence! For the Asmat, who live deep in their ideas of ghosts from the underworld, it must have seemed as if by killing a white man they had opened the gates of hell. Very frightened by the helicopters and all the hustle and bustle, hundreds of villagers hide deep in the forest. They want to escape from the evil spirits.

And then, only a few months later, a cholera pandemic strikes the Asmat region. More people have died than any Asmat has ever seen before. And once again, helicopters flew over their territory – helicopters of the Australian Army, which tried to help to cope with the pandemic situation.

Hundreds dead, evil helicopters harassing their villages – the shock for the Asmat must have been unprecedented. So they came to the conclusion: “If you tell the story, you will die”. Since then, the story remains untold, buried with the bones of Michael until today.

Interested in an exciting journey to the Asmat? On our annual expedition to the eastern coastal Asmat we follow the tracks of Rockefeller and also visit the infamous village of Otsjanep. Click here for the program: Eastern Coastal Asmat Tour